Author Jackson P. Brown on Creative Writing, Industry Access and Endurance

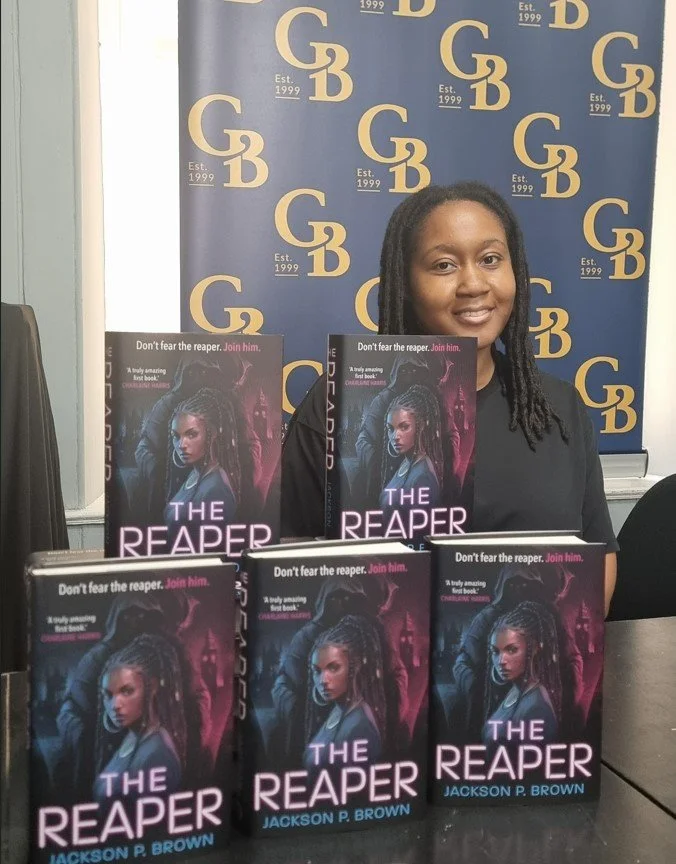

WriteNow 2020 Winner Jackson P. Brown with her published book 'The Reaper'

For Black British writers, doors open quietly, if at all, and when they do, you are expected to enter gratefully, not critically. Against that backdrop, Jackson P. Brown’s journey feels instructive; not because it is rare, but because of how honestly she speaks about what it takes to endure, succeed and navigate the complex industry of publishing.

Brown was selected for Penguin’s WriteNow programme during lock-down, applying at a moment when industries were simultaneously disrupted and felt exposed. That year, after several competitive rounds and months of waiting, she was chosen from thousands of applicants, an experience that would eventually lead to the publication of their debut novel The Reaper. But the significance of that moment, Brown makes clear, wasn’t just the outcome. It was what it confirmed: that her voice, stories, and place in publishing were not conditional.

There is a particular exhaustion that can come from being talented in an industry that can seem inaccessible and confusing to navigate. Jackson P. Brown doesn’t dress that truth up. Reflecting on how publishing actually operates beneath its public-facing mythology, she says plainly, “This industry is not really a meritocracy. It is about your connections, it is about your access.” Jackson speaks with the clarity of someone who has lived within both the promise and the limits of traditional publishing. Her journey, from submitting a manuscript during lock-down to being published by Penguin Random House, was never framed by inevitability. Instead, it was shaped by doubt, persistence, and an understanding that belief in your work often has to come before anyone else offers it to you. Looking back at that moment, she admits, “I always thought it was like my last kind of chance with that book… but I really believed it at the time. I believed in my writing.”

Before publishing, Brown’s background was not industry-facing. She studied Sociology and English Literature which contributed to further igniting the passion for writing, but her work at that time remained something private, pursued without institutional validation. As she explains, “I hadn’t written in any professional capacity, but it was a hobby… I always wanted to be traditionally published, so I wanted to be a novelist for as long as I remember, really.” That desire existed alongside rejection. Her manuscript, a dystopia set in London, was previously presented with little success, and the silence was familiar. “I wasn’t really getting a lot of bites from agents… I was kind of getting a lot of objections,” she recalls. Jackson kept going, refusing to internalise those objections as a verdict on their talent. Drawing a hard, clear line between rejection being a reflection of inadequacy, offering sage advice rooted in lived experience: “You have to remember that you do, in some sense, have to work harder, but it’s important not to take anything personally, because unfortunately, it’s probably not your writing, it’s that the person that you’re submitting to just might not understand you.” That distinction, between misunderstanding and perceived ‘failure’, is one many under-represented writers are not always taught to make, feeding into misplaced imposter syndrome. Once that distinction is firmly rooted, it is replaced by being securely planted in self-belief.

Brown is particularly candid when discussing the post-2020 publishing landscape, where public commitments to diversity did not translate into long-term structural change. Situating her experience within a wider industry pattern, she notes, “Since 2020… the acquisitions of Black authors get a chance to be published, it just dropped.” She describes scrolling through publishers’ previews of upcoming lists recently and noticing what, and who, was missing. “They’ve started to post their little teasers for what’s coming out next year in 2026 and I hadn’t seen any of their Black authors,” she says, before adding pointedly, “You can’t be telling me that for the whole of next year you have no Black authors.” For Brown, the issue isn’t just acquisition, but investment. She makes this difference clear when she says, “The fact that you’re not doing it for any Black writers means that you don’t intend for any of their books to be a splash or you’re not going to put the investment behind them.”

Brown goes on to connect this to the closed ecosystems of BookTok and Bookstagram, spaces that increasingly shape commercial success but remain racially skewed. As she observes, “They have their favourite book influencers… but they tend to be like white reviewers,” before highlighting the missed opportunity: “There’s a massive interest in Black reviewers who will hype it and go crazy over it… but they don’t get looped in in the same way.” The result, she argues, becomes cyclical and self-justifying. “The sales of Black authors can at times tend to be fewer,” Brown explains, “and they just say, well we were right then not to promote you.” But with the investment not always made toward these authors the outcome can not really be comparable, but positively Jackson highlights the essential skill and empowerment of self-promotion, “Once they see how invested you are in yourself and self-motivated, then they'll see that, well, they're investing themselves, I will also invest in them,” and goes on further, “There's things I was able to do for myself when I felt it wasn't quite working out how I’d hoped during my debut year. I built my own connections, sending out copies of my book to influencers myself. I'd set up a pre-order campaign with an indie bookseller… make your own opportunity because for them it's another book that was published in the year. But for you, this is your only debut book.”

One of Jackson’s most transformative aspects of being recognised by the industry wasn’t just opportunity, it was affirmation. Reflecting on what stayed with her most, she says, “Just someone outside to say to me, you know, you have potential. And I think that does make a difference when someone in the professional capacity can tell you that… a second voice to say you're on the right track, and actually had someone who believed in me and was passionate about my writing.” Equally, Jackson is careful not to romanticise this moment; validation doesn’t erase barriers. But it does interrupt the inherent self-questioning many marginalised writers are conditioned to carry. As Brown puts it, “We kind of always go around feeling so grateful all the time… when we have just as much of a right as anybody else.” A contrasting example of this was highlighted, going into how easily others are ushered into the industry, recalling, “There was a booktokker; a White man who just got handed a two book deal because he went viral… literally just after a month or so on TikTok.” Rather than resentment, Jackson’s conclusion is clarity. “If that’s how [some publishers] can just hand it out to people, then you don’t need to worry about ‘am I talented enough?’ You just need to find your champion because you absolutely deserve to be there.”

Beyond her own work, Brown is also the founder of Black Girl Writers, a community created in response to absence and transmute that into the inverse of presence and abundance. Explaining the motivation behind it, she says, “If you don’t see the ecosystems that you want… the solution is to start building one that you want.” Through free Q&As and direct access to publishing professionals, the aim is transparency, what Brown describes as “lifting the veil of publishing.” But even here, she remains realistic about how power operates. “When the same people consistently turn up,” she notes, “the editors will recognise certain people… it provides an opportunity for those authors to start building networks.” So there is an importance in looking out for opportunities of visibility and building your network; be in the room.

Publishing, for Brown, is less about passion than stamina. “It’s something that you have to constantly be enduring,” she says, acknowledging why many Black writers eventually turn away from traditional publishing altogether. “I fully understand that… people say, Trad Pub clearly isn’t for us.” But there is a danger in absence. “The fewer of us out in traditional publishing the fewer of us that can try to enact some sort of change.” What sustained her was refusing passivity, describing how she adapted when institutional support felt limited, and that distinction, between institutional priority and personal stakes, shapes everything. “You might not be a 10,000 copy bestseller,” she reflects, “but you want to feel proud of something.” As a Black British fantasy writer, Brown is aware of representation within the genre and highlights recent shifts. Noting the changes she’s witnessed, she says, “There’s been such an amazing crop of new Black British writers in the space.” Her advice to younger writers is grounded in visibility and research. “When you see yourself, then you can feel like you can be part of that as well,” she says, encouraging writers to read widely, follow Black authors, and track who is being published now. “It is inspiring.”

To end, Brown is clear that what WriteNow offered her at a crucial moment was not a shortcut, but something far more sustaining: belief, access and momentum, alongside the opportunity to build lasting editorial relationships and a deeper understanding of how the industry actually works beyond the surface. Now in its tenth year, Penguin’s WriteNow scheme has supported thousands of under-represented writers, offering free industry workshops, one-to-one editorial feedback, and a year-long development programme for a final cohort, with more than 30 writers going on to secure publishing deals. This year’s programme focuses on children’s books for ages 0–12 and remains open to writers from backgrounds under-represented on the nation’s bookshelves. For those considering applying, Brown’s advice is grounded and clear: show up fully, use every opportunity to connect, and trust that your voice deserves to be taken seriously.

Applications for this year’s programme opened on Tuesday 28th October and close at midnight on Wednesday 7th January 2026. With the first step simply being to submit the work you believe in, writers interested in applying can find out more information at www.penguin.co.uk/writenow.